The Trans-Pacific Partnership: What’s in it for Canada?

About the Business Council

The Business Council of Canada brings business leaders together to shape public policy in the interests of a stronger Canada and a better world. Founded in 1976, the Business Council is a non-profit, non-partisan organization composed of the chief executives of Canada’s leading enterprises, representing companies from every region and sector of the economy.

Through supply chain partnerships, service contracts and mentoring programs, Business Council members support many hundreds of thousands of small businesses and entrepreneurs in communities of all sizes across Canada.

Why the TPP Matters

The world needs a new kind of trade deal. Rapid technological advancement, multi-country supply chains, e-commerce and the global services sector demand agreements that reflect the reality of business and trade in the twenty-first century.

Negotiated over 7 years, the Trans-Pacific Partnership establishes a new economic framework to promote growth, trade and jobs across the Asia-Pacific region, while addressing important sustainable development concerns.

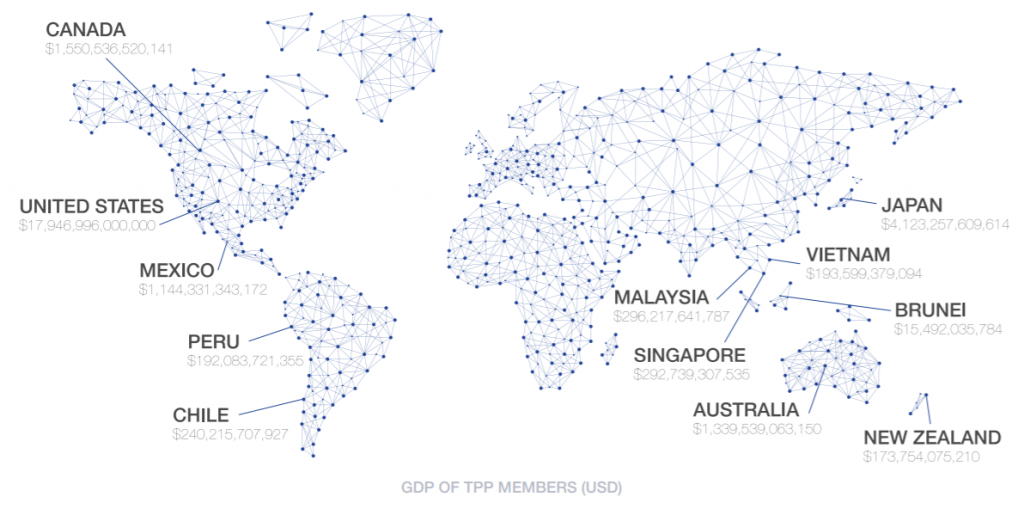

Its 12 signatories include Peru, Australia, Vietnam, Malaysia, Canada, Mexico, New Zealand, Brunei, Singapore, United States, Chile and Japan. A number of other countries have expressed interest in joining the negotiations, including South Korea, Philippines, Laos, Colombia, Indonesia, Cambodia, Bangladesh, Thailand and India.

How big is the TPP?

All told, TPP countries are home to over 840 million people, and have a combined GDP of nearly $29 trillion USD. Together, these 12 countries are responsible for approximately 40 per cent of the world’s economic output.

Economic modelling estimates that in Canada alone, the TPP could yield annual income gains of $9.9 billion USD and increase exports by $15.7 billion USD.

Concluding an ambitious, high-quality TPP agreement is the most efficient way for Canada to deepen its integration with other Asian-Pacific economies and take advantage of the fast-growing markets.

Canada’s Opportunity

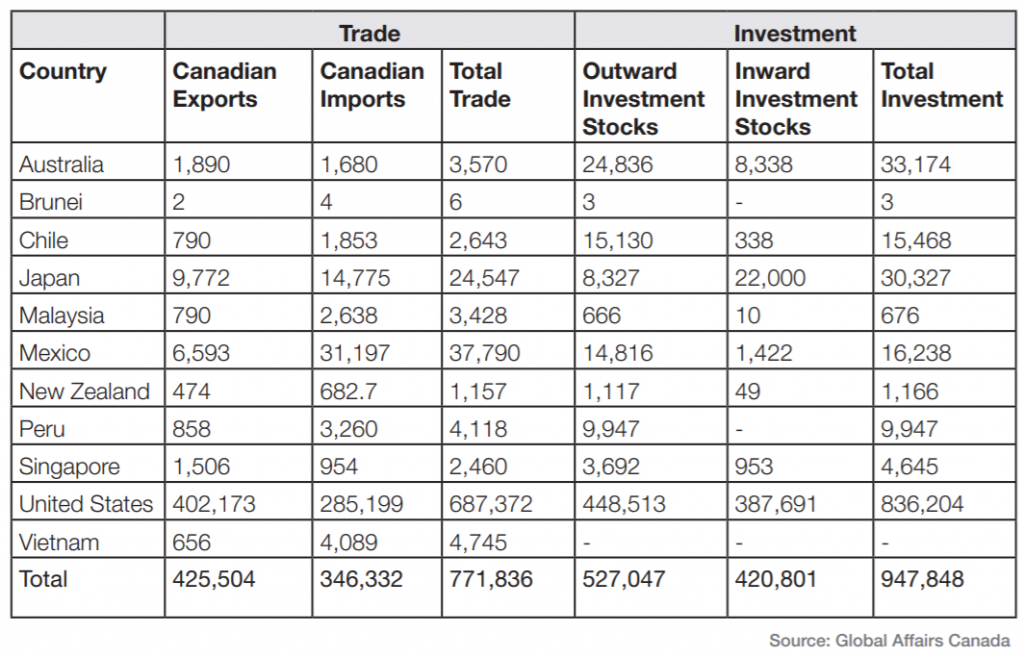

Canada’s trade and investment

TPP Members (millions), 2015

The TPP builds on Canada’s history of developing strong trade agreements: one in five Canadian jobs depend on exports. Worth $775 billion in 2015, Canada’s total bilateral merchandise trade with TPP members represented 73 per cent of Canada’s total merchandise trade that year, with the U.S. forming the vast majority. TPP countries are also a significant source of both inward and outward stocks of Canadian investment, with two-way investment of over $981 billion in 2015.

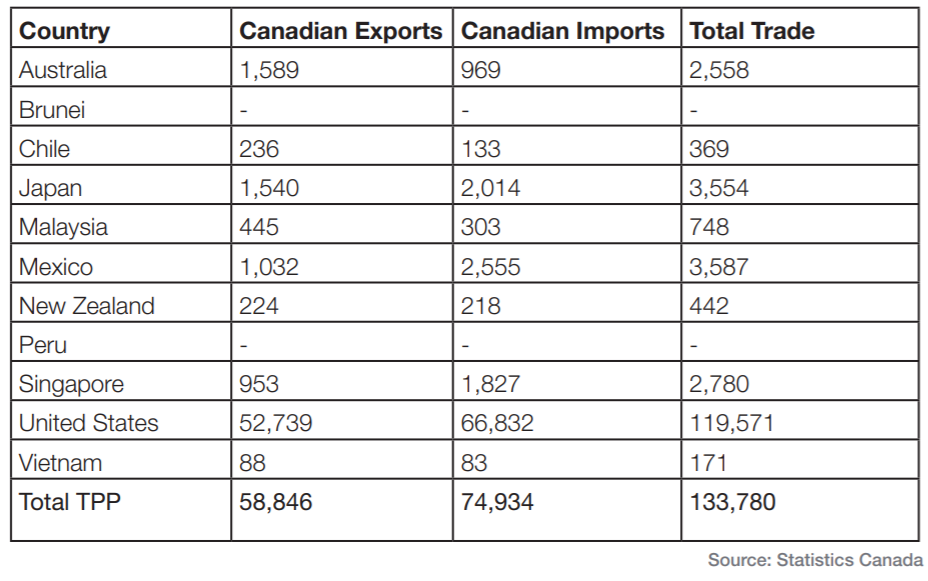

Canadian services trade

TPP Members (millions), 2014

An important and often overlooked component of Canada’s trade with the world is services trade. The services sector accounts for 72 per cent of Canadian GDP, 75 per cent of employment and 90 per cent of new job creation.

Canada exported nearly $95.7 billion in services internationally in 2014, with services exports to TPP members growing by 8 per cent between 2007 and 2011.

Examples of service sector industries include retail, banks, hotels, real estate, education, health care, computer and IT services, sports and recreation and media.

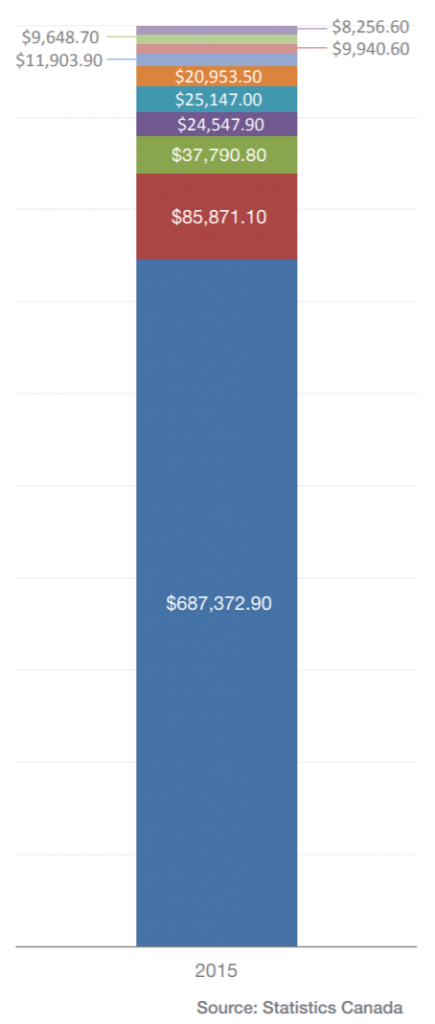

Canada’s top merchandise trade partners

(millions of CAD)

According to the World Bank, the trade of goods and services account for 65.8 per cent of Canadian GDP in 2015. But for the most part, Canada’s trade is rooted in North America. Over 65 per cent of Canada’s trade goes to the U.S.

Although the size and proximity of the U.S. means it is likely to remain Canada’s number one trading partner, diversifying Canadian export markets should be a priority. The Bank of Canada has repeatedly called on Canada to liberalize trade. In a recent speech, Governor Poloz noted recently that in a low-growth world, trade liberalisation efforts initiatives such as the TPP, the Canada-EU trade agreement and the removal of interprovincial trade barriers could have a significant impact on economic growth, year after year.

Beyond the risks of putting two thirds of Canada’s trading eggs into the American basket, there are tremendous opportunities for Canada’s resource, manufacturing and services sectors in other TPP member countries.

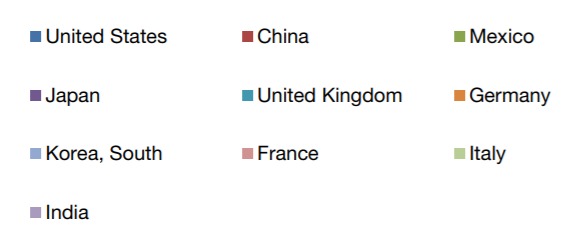

Share of the global middle class

Over the next twenty years, Asia’s middle class will demand energy and natural resources, financial services, education, cleaner technology and in fact, by 2030, 66 per cent of the global middle class is projected to live in the Asia-Pacific region.

Although the federal government has recently taken encouraging steps to building a stronger relationship with China, Canada remains behind the curve in seizing the opportunities of Asia’s development. Trade between Canada and Asia-Pacific countries has increased since 2011, but the region still represents only 16 per cent of Canada’s total bilateral merchandise trade. If Canada is to take advantage of the Pacific Century, trade and investment liberalization must be a priority: currently, our only trade agreement in the Asia-Pacific is with South Korea.

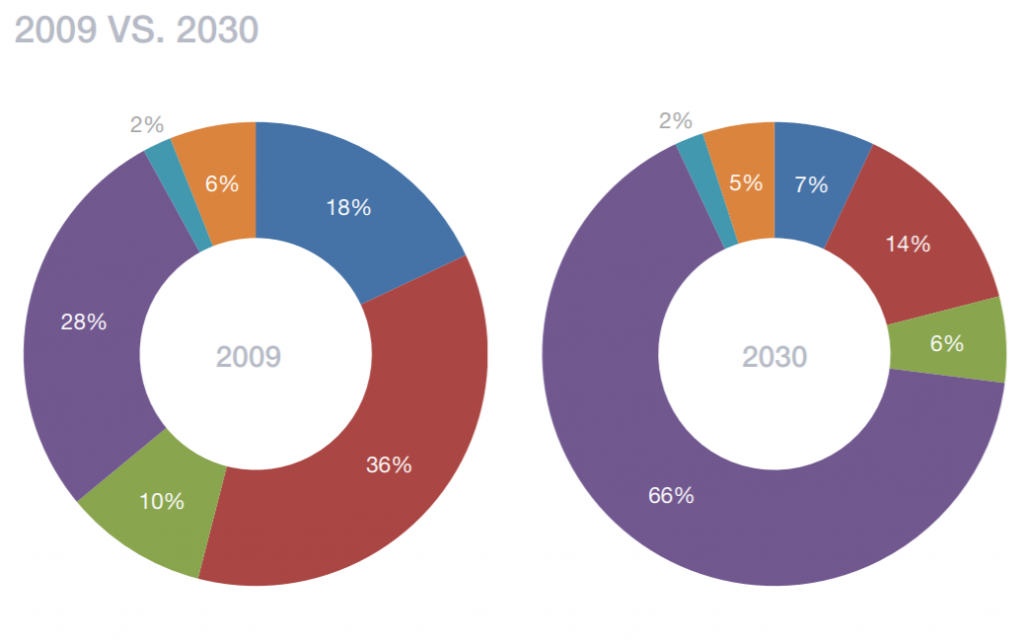

Where Canada trades

Measured in billions (USD)

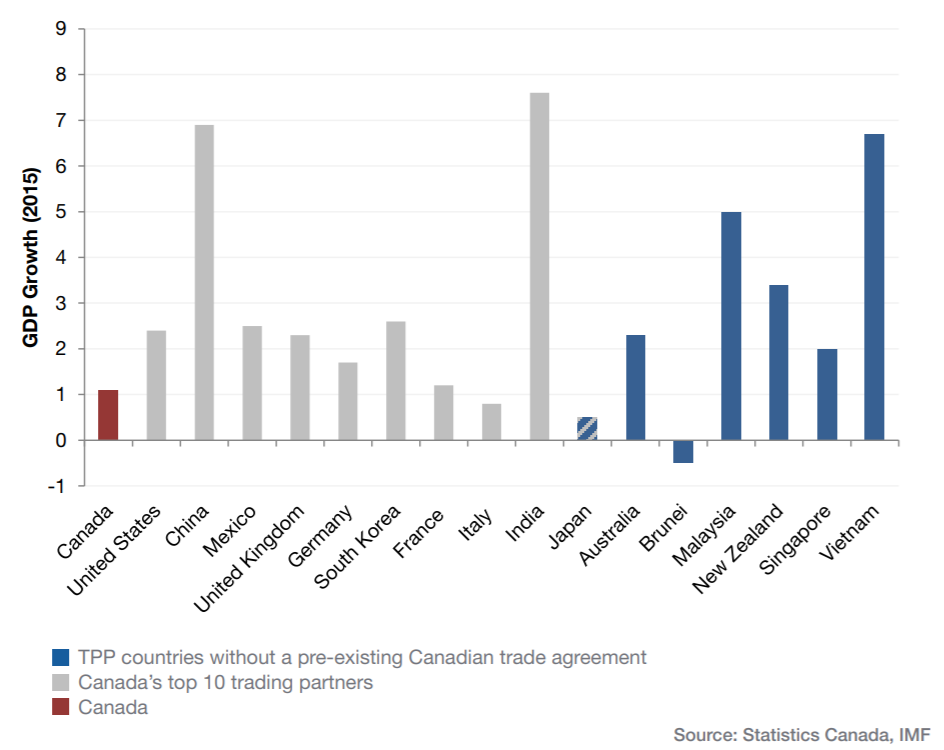

Projected GDP Growth

Canada’s top ten trading partners vs. TPP countries

One of TPP’s primary advantages for Canada is that it will immediately lock in trade agreements with a number of markets, including Australia, Brunei, Japan, Malaysia, New Zealand, Singapore and Vietnam. Home to 283 million people, these countries had a GDP of $6.4 trillion USD in 2015. For example, Vietnam and Malaysia are growing at a rate of 6.7 per cent and 5 per cent, compared to the global average of 2.46 percent.

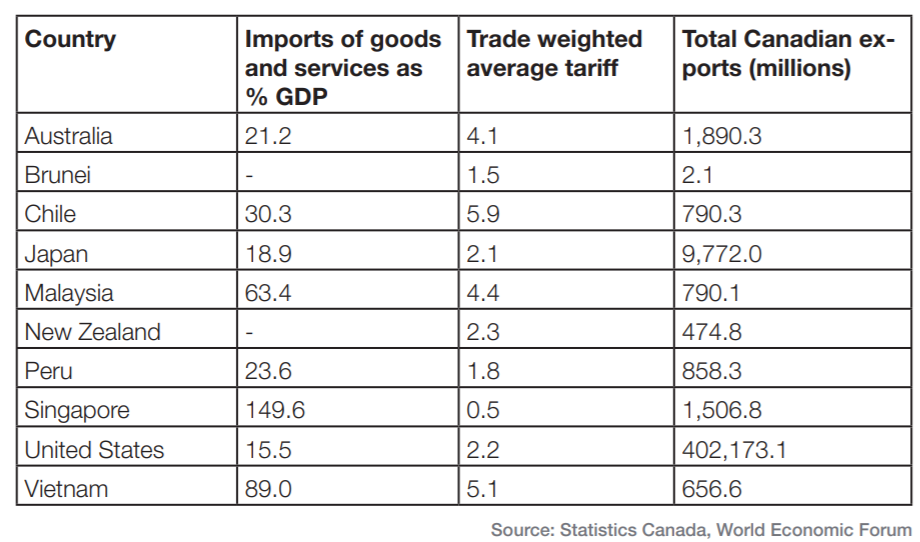

Trade openness

While most markets have relatively low levels of traditional trade protection, Japan offers Canada the most new market potential with an average trade weighted tariff of 2.1 per cent and low import penetration (18.9 per cent of GDP).

According to the World Bank, the average TPP-stimulated growth will be 1.1 per cent. At the high end, the TPP will boost Vietnam’s real GDP by 10 per cent and Malaysia’s by eight per cent. Among NAFTA countries, the average growth rate is projected to be closer to 0.6 per cent of real GDP.

An analysis by Global Affairs Canada found that the TPP is expected to increase Canadian GDP by 0.13 per cent by 2040. The C.D. Howe Institute forecasts a slightly smaller gain of 0.08 per cent by 2035, driven by an increase in two-way trade with TPP partners of about $4.3 billion as of 2035.

Setting Global Goals

Beyond the direct and measurable increase in Canadian GDP and job growth through trade, the Trans-Pacific Partnership is a watershed moment for global economic integration.

Significant improvements in the business climate of TPP signatories will boost business for Canadian companies, as the TPP provides an opportunity for emerging economies to adopt transparent, non-discriminatory policies to build sustainable growth.

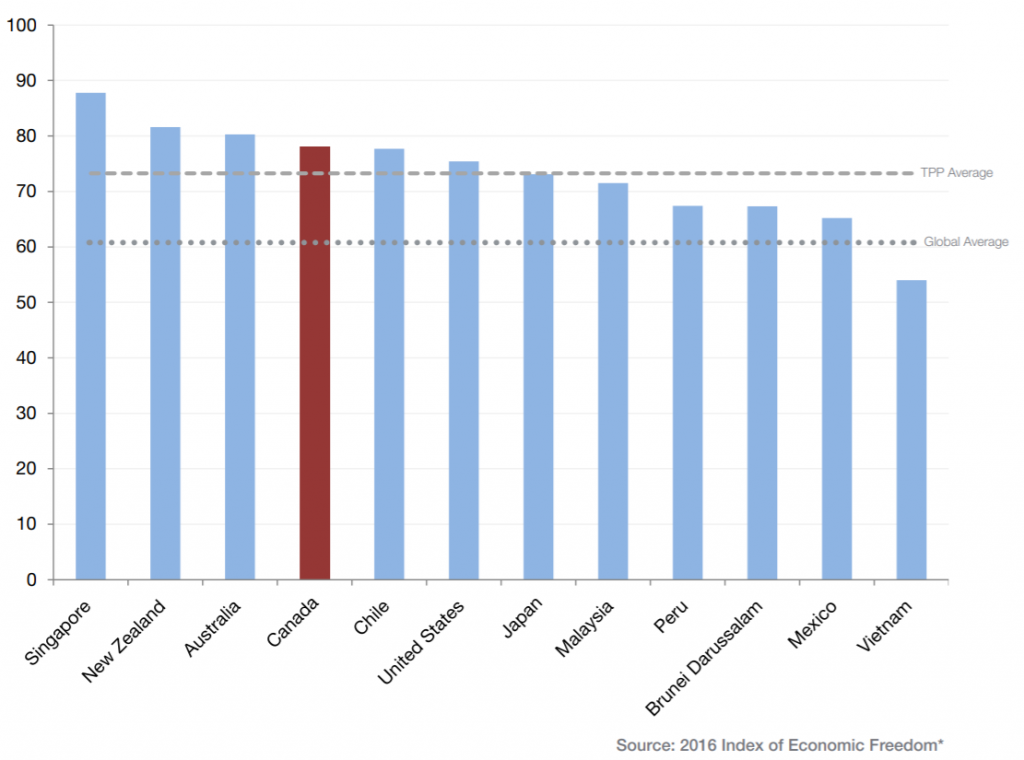

Market freedom

Measured in economic freedom score

Most TPP countries, including Singapore, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, Malaysia, Chile, the U.S. and Japan are among the world’s top 38 “free and mostly free” economies, according to the 2016 Index of Economic Freedom. Sporting high levels of business, trade, investment and financial freedom, these countries will develop the roadmap of behaviour for emerging economies within the trade zone.

Only Vietnam and Brunei fall below the “mostly free” threshold. The TPP has the potential to improve both the regulatory framework that influences business freedom and the level of openness in the market. Domestic reforms that enhance market freedom will provide greater certainty for Canadian businesses trading with or investing in these economies.

Rather than a series of individual deals with each country, the TPP would synchronize areas like market access, investment and intellectual property, regulatory cooperation, e-commerce and government procurement across 12 countries. This unified trade “rule book” would level the playing field; ensuring Canadian companies have the same advantages and opportunities as their competitors in the region.

Beyond that, the TPP builds on the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in important ways, ensuring that Canadian exporters retain preferential access to customers in the US and Mexico and including chapters on environmental commitments and labour rights. To preserve our most critical trade relationships, Canada must remain on the same page as our Mexican and American partners.

Further Reading

Economic impact of Canada’s potential participation in the Trans-Pacific Partnership agreement

Global Affairs Canada

September 2016

Debunking alarmism over the TPP and IP:

Why the Trans-Pacific Partnership is a good deal for Canadian innovators

Richard C. Owen

January 2016

The economic effects of the Trans-Pacific Partnership: new estimates

Peter A. Petri, and Michael G. Plummer

January 2016

Potential macroeconomic implications of the Trans-Pacific Partnership

The World Bank

January 2016

Better in than out? Canada and the Trans-Pacific Partnership

Dan Ciuriak, Ali Dadkhah, and Jingliang Xiao

April 2016

Why the TPP is such a big—and good—deal for Canada

Trevor Tombe

October 2015