Effective Management of Human Capital in Schools: Recommendations to Strengthen the Teaching Position

Introduction

There is much to be proud of in Canada’s system of public education. Over the past decade, the national high school graduation rate has risen from 72 per cent to 78 per cent (Statistics Canada, 2012a), an increase that reflects the achievements of tens of thousands of young people. International evidence indicates that Canada enjoys one of the most effective public education systems in the world, with one of the smallest gaps between the performance of its strongest and weakest students (OECD, 2010). And all of this is being achieved with one of the most diverse student populations to be found anywhere on the planet.

Yet despite this track record, public satisfaction with Canada’s public school system tends to be low. A recent poll by Ipsos Reid (2012) found that 60 per cent of Canadians would give the public education system a grade of C or lower. The same poll suggested that two-thirds of parents would take their children out of the public system and send them to a private school if money was not a concern.

What explains this disconnect? To some extent, increased expectations may be to blame: As our schools have become more successful, we have come to expect them to do even more. Yet that cannot explain all of the dissatisfaction. My own view is that an individual’s perceptions of the education system are driven more by personal experience than by statistics or Canada’s overall performance in international assessments. And when we are talking about people’s experience with public education, we are mainly talking about their interactions with teachers. That is to say, strong support for public education depends largely on the quality of the teachers we remember having ourselves, as well as the quality of the teachers our children have now.

There is good reason for this. Research on teacher effectiveness has underscored two key if perhaps obvious findings: teachers matter, and yet teacher quality varies considerably.

Teachers Matter

For many years, researchers believed that factors outside of the classroom were the main determinants of student achievement (see, for example, Coleman et al., 1966). These included social class, innate intelligence, family background and community dynamics, among other influences. But while these factors are undeniably important, they do not explain why schools with similar student populations can vary widely in the achievement of their students (Sammons, Hillman & Mortimore, 2005; Willms and Raudenbush, 1989). More recent research suggests that the most powerful influence on student learning is the effectiveness of individual teachers (Clotfelter, Ladd & Vigor, 2007; Ferguson & Ladd, 1996; Hattie, 2002; Haycock, 1998; Nye, Hedges & Konstantopoulos, 2004; Rice, 2003; Rivkin, Hanushek & Kain, 2005; Sanders & Rivers, 1996; Whitehurst, 2002). The evidence also suggests that exposure to above-average teachers for a sustained period of time can overcome the achievement gap between students from higher- and lower-income families (Bracey, 2004; Rivkin, Hanushek & Kain, 2001).

The impact that good teachers have on their students can be profound. A landmark U.S. study (Chetty, Friedman & Rockoff, 2011) that tracked 2.5 million students from a large urban school district over a 20-year period found that the best teachers (defined by the researchers as “high value-added”) increased the earnings of each of their students by an average of $25,000 over a lifetime. This translates into an increase of $600,000 in economic gains for a class of 24. The students of such teachers were also less likely to experience teen pregnancy, more likely to attend university or college, and to save more for retirement compared with students who were taught by average or below-average teachers. Other studies suggest that higher levels of educational achievement are associated with lower levels of incarceration and improved health. It should thus be clear that teachers are among a society’s most important resources.

Teacher quality varies considerably

The challenge for education policy is that the quality of teaching in our schools varies considerably. The same landmark study cited above (Chetty, Friedman & Rockoff, 2011) found that students who were exposed to ineffective teachers earned $50,000 less over their lifetimes compared with students who were taught by average teachers. This translates into an economic loss of $1.2 million per class. Simply put, it is ruinous economic policy to allow ineffective teachers to teach our students.

Excellent teachers are far from the exception in Canada’s public schools. Still, it takes only a few encounters with ineffective teachers for students and parents to lose confidence in the public education system. The fundamental issue is that, for the most part, Canadian education systems do not strategically manage their human capital. Human resource policies in our school systems are more often guided by historical tradition and bureaucratic expediency, rather than by a devotion to excellence and effectiveness. These ingrained practices constitute a significant drag on the quality of teaching in our schools.

This report puts forward a series of recommendations to improve the way Canadian schools manage their most important resource. A strategic approach to managing this resource, as outlined in Odden (2011), requires that school administrators:

- recruit effective teachers for all schools and classrooms;

- provide training that raises the quality of teaching, improves student achievement, and reduces achievement gaps;

- recognize, reward and retain the teachers who are successful in meeting these objectives; and

- let go of those teachers who cannot meet the objectives.

In line with that approach, this report will examine the following three policy areas as they relate to teachers: recruitment and hiring, evaluation, and pay.

Recruitment and Hiring

Of the factors that are under the control of education policy makers, nothing influences student outcomes more than the policies that determine who is hired to teach and whether that teacher is retained or dismissed (Darling-Hammond, 2003; Harris, 2004). We cannot hope to improve student achievement without ensuring that our schools are staffed with talented educators.

School staffing decisions also carry significant financial implications. If a teacher turns out to be a poor fit for his or her school or district and chooses to resign, the costs arising from this turnover can be as much as $78,000 per teacher (Carroll, 2007). Dismissing an ineffective teacher can be even more expensive – upwards of $200,000, according to a study in New York State during the 1990s (Kahlenberg, 2006). In total, teacher turnover costs the U.S. an estimated $7 billion a year. One way to contain these costs is to hire good teachers from the start. Research suggests that highly effective teachers are less likely than others to leave their jobs (Boyd et al., 2011; Feng & Sass 2011; Goldhaber, Gross, & Player, 2007;Hanushek et al., 2005; West & Chingos 2009).

In Canada, each province and territory sets its own certification criteria for teachers. Authority for the hiring of teachers is delegated to local school boards; in practice, staffing decisions are usually made by the school principal. Different school boards and principals can and do adopt different approaches to hiring, not all of which are equally effective. Schools that generate the greatest increases in student achievement have been shown to use a different approach to teacher recruitment than that used by schools with weaker outcomes (Loeb, Kalogrides & Beteille, 2012).

Recommendation 1- Hiring decisions should continue to be made locally by school principals

Although school boards can sometimes play a useful role in pre-screening eligible candidates, hiring decisions are best left in the hands of the school principal. Indeed, much international evidence indicates that students tend to perform better when schools have autonomy in personnel decisions (Clark, 2005; Esekeland and Filmer, 2005; Robin & Sprietsma, 2003; Wößmann, 2003). Given that, it is difficult to rationalize the Ontario government’s recent policy change requiring principals to hire for long-term assignments based on seniority. This effectively forces principals to hire based on teacher seniority, rather than talent or effectiveness. (In September 2013, Ontario’s Ministry of Education announced that it is reviewing the policy.)

Recommendation 2 – Hiring should be based on merit, not seniority

One argument in favour of seniority-based hiring is that teachers with more experience are presumed to be more effective. Yet there is no empirical evidence to support this view; on the contrary, research shows that longevity in the classroom is a poor predictor of how well a teacher can actually teach (Boyd, Grossman, Lankford, Loeb & Wyckaff, 2006; ; Hanushek, 2003; Hanushek, Kain, O’Brien & Rivkin, 2005; Kane, Rockoff, & Staiger, 2006; Rivkin, Hanushek & Kain, 2005; Rockoff, 2004). Granted, there is evidence that effectiveness tends to increase during a teacher’s first few years on the job. After this initial period, however, teacher effectiveness typically plateaus, and sometimes even declines in later years.

Why, then, did the Ontario government decide to emphasize seniority in its hiring policy? The policy change was a bargaining chip during the most recent round of negotiations with one of its teachers’ unions. Unions love the concept of seniority because it favours existing employees and hence increases the value of the union to its members. But while seniority-based hiring is in the interest of teachers’ unions, it is not in the best interest of students. By undermining the authority of principals to select teachers who are best suited to their schools, and by denying employment opportunities to talented but less experienced young teachers, seniority-based hiring ultimately results in less effective schools.

Recommendation 3 – Hiring decisions should be based not just on resumes and interviews, but on demonstrated teaching ability

As in many fields, the first step in the process of hiring a teacher is typically to assess each applicant’s resume; the second step usually involves interviews with a select group of candidates. Unfortunately, the fact that someone has earned certification in the required subject area and possesses teaching experience is generally not a good indicator of teacher quality (Rivkin, Hanushek, & Kain, 2005; Rockoff, 2004). Similarly, interviews are well recognized as poor predictors of job performance (Conway, Jako, & Goodman, 1995; McDaniel, Whetzel, Schmidt, & Maurer, 1994; Posthuma, Moregeson & Campion, 2002; Schmidt & Hunter, 1998; Wilk & Cappelli, 2003). They favour candidates who have the ability to make a good impression, not necessarily those who are capable of teaching well.

Given the high stakes, this is a serious problem. We simply cannot allow such an important decision to be driven by impressions and intuition. That is why an increasing number of school districts are introducing teaching demonstrations to the hiring process. The applicant might be asked to submit a video recording from his or her previous teaching position – analogous to an actor’s audition reel. Alternatively, the candidate could be assigned to conduct a lesson in a class that matches the grade level or subject area for which he or she is applying. Either approach would provide school administrators with a much clearer understanding of the candidate’s ability to teach and to relate to students, and is well worth the additional time and effort.

Recommendation 4 – Our best teachers should be deployed to teach our neediest students

The final aspect of teacher hiring and recruitment that requires attention is that of teacher distribution and assignment. If we are serious about wanting to close the achievement gaps that exist between students from high- and low-income families and between students from different racial and cultural backgrounds, we have an obligation to ensure that our neediest students are assigned the most effective teachers possible.

The inequitable distribution of teachers among schools and classrooms has long been a problem in public education (Imazeki & Goe, 2009). In general, U.S. studies have found that schools in lower income areas or with higher concentrations of minority students are more likely to have lower quality teachers (Betts, Rueben, & Danenberg, 2000; Clotfelter, Ladd, & Vigor, 2005; DeAngelis, Presley, & White, 2005; Iatarola & Stiefel, 2003; Lankford , Loeb, & Wyckoff, 2002; Owen, 1972; Peske & Haycock, 2006; Summers & Wolfe, 1976). Although no similar Canadian research has been conducted, anecdotal evidence suggests that Canadian schools exhibit the same pattern.

There are many reasons why this can happen. One is that teachers often prefer to teach students similar to themselves; in practice, that means teaching in schools with high concentrations of high-achieving, middle-class students (Falch & Strom, 2005; Hanushek & Rivkin, 2007; Lankford, Loeb, & Wyckoff 2002; Scafidi, Sjoquistb, & Stinebrickner, 2007; Smithers & Robinson, 2004, 2005.) When teachers talk about working at a “good” school, this is usually what they mean.

Inequities in teacher distribution are also explained by pressure from parents in higher income neighbourhoods to ensure that the best teachers remain in their own schools (Laine, Behrstock-Sherratt, & Lasagna, 2011). Parents in less well-off neighbourhoods tend not to possess the same level of influence and social capital.

Inequitable teacher distribution also occurs within schools. For example, newer, less experienced teachers are frequently assigned to teach the most challenging students, who are often found in lower academic streams (Clotfelter, Ladd & Vigor, 2006; Feng, 2010; Rothstein, 2009). Conversely, teachers with more experience are assigned classes in higher academic streams that attract higher achieving students. This is done without regard to actual effectiveness and is usually justified on grounds of seniority. But while this arrangement may please senior teachers, it is not in the best interest of students. Indeed, this type of teacher allocation has been shown to worsen student achievement gaps (Feng, 2010; Kalogrides, Loeb & Beteille, 2011).

Thus school leaders need to take deliberate steps to ensure that our neediest schools and neediest students are assigned the best teachers possible. This is what the most effective school systems and schools do (Loeb, Kalogrides & Beteille, 2012). We simply cannot allow an inequitable distribution of teachers to result from parental pressure or norms regarding seniority.

Teacher Evaluation

Effective systems of teacher evaluation are essential if we are to improve the quality of teaching in our schools. Proper evaluation helps to ensure that school administrators make sound staffing decisions with regard to tenure, promotion and dismissal. It also provides a source of information that can guide professional development for teachers. This latter point is one that teachers and teachers’ unions often overlook. For example, the 2012-2013 Members’ Guide of the British Columbia Teachers’ Federation states that, “the evaluation of members should be based on the assumption of professional competence and, hence, formal evaluation should not occur unless the assumption is questioned or a formal evaluation is requested by the member” (p. 155). This is myopic. Teacher evaluation is not simply a means to single out poorly performing teachers (although such problems must be addressed). All teachers need – and can benefit from – regular assessments and feedback.

As they exist today in Canada, teacher evaluations tend to be time-consuming but of low quality (Odden, 2011). This is a point on which both administrators and teachers can agree. For example, a study of the evaluation process in Newfoundland found that teachers viewed it as unsupportive of professional growth (Rowe, 2000). A similar study, in Ontario, concluded that most teachers considered their evaluations to be “disorganized, inconsistently conducted and above all unfair” (Larsen, 2009). My own research suggests that school administrators are not convinced that the evaluations they conduct accurately assess teacher performance or result in substantial improvements in teacher effectiveness (Maharaj, 2013).

The obvious question is why we would continue doing something that nearly everyone involved recognizes is of little benefit. Why waste the time of teachers and administrators?

Problems with current approaches to teacher evaluation

Before considering options for reform in this area, we should address why current approaches to teacher evaluation are ineffective. There are a number of reasons:

- Evaluations are not representative of actual teaching performance. Teacher appraisals often consist of a single, pre-arranged visit to the classroom by the principal. Since the visit is scheduled well in advance, teachers often put on a show, one that bears little resemblance to a typical class. Here is how one researcher described a similar system of evaluation in a U.S. school:

- In preparation for an evaluation visit, a teacher had distributed a special student handout to her class. When she heard over the intercom that the principal had to postpone his observation, she collected the worksheet from students and proceeded with the “normal” lesson. (Marshall, 2009, p. 23)

- Evaluations are infrequent. Most Canadian teachers are rarely if ever evaluated. For example, Ontario requires its teachers to be evaluated once every five years, while Alberta does not require regular evaluations. This is simply inadequate. It should be unacceptable for professionals in any field to go years without taking a comprehensive look at their practice. Regardless of their ability level or years of experience, teachers deserve and need ongoing feedback.

- Ratings do not differentiate performance. Most evaluations use a two-level rating scale that does not meaningfully differentiate performance. Typically this means a mark of either “satisfactory” or “unsatisfactory”. Since virtually all teachers are rated “satisfactory”, such a scale essentially provides no useful information, to the teacher or anyone else. As stated by Marshall (2009, p. 30): “This kind of evaluation is unlikely to motivate a mediocre teacher to improve and spur a good teacher to strive for excellence”.

- Evaluators are not properly trained. Administrators in Canadian schools receive remarkably little training in how to conduct accurate, meaningful evaluations (Bolger & Vail, 2003; Maharaj, 2013). There appears to be an implicit assumption that someone who is qualified to become a school administrator by definition is capable of conducting a proper evaluation of teacher performance. However there is no evidence to support this assumption. Perhaps this explains why many teachers report not feeling confident in the evaluative abilities of their administrators (Barnett, 2006; Larsen, 2009).

- Evaluations lack consequences. The results of teacher evaluations are rarely used except to justify the dismissal of an egregiously poor-quality teacher. It is understandable, then, that teachers and teachers’ unions tend to regard evaluations primarily as a means of singling out inadequate teachers. One might also conclude that our school systems are largely indifferent to teacher effectiveness, except when it comes to removing the most obvious inept teachers. If the highest rating one can hope to earn is “satisfactory”, the system provides little incentive to improve one’s performance. As one administrator put it:

- I think this speaks to the fact that as long as you are given a satisfactory appraisal, teachers are satisfied. They understand that it matters little. TPAs [Teacher Performance Appraisals] are never even mentioned when a candidate is applying for a new job with a new school and administrators are looking for a reference. I have never seen a question that asks ‘How was their last TPA?’ (Maharaj, 2013, p. 39)

- Evaluations are not tied to professional development. Evaluations would be useful if they were used to help focus a teacher’s professional development on areas identified as needing improvement. Yet this does not happen in our schools. Except in the case of a teacher who is at risk of being terminated, there is no follow-up. And since evaluations are infrequent, any recommendations that do emerge are usually long forgotten by the time the next one comes around. This helps to explain why the current approach to teacher evaluations tends not to generate performance improvements. As another administrator noted:

- Once teachers have their copy of the evaluation, it is totally within their control whether they want to pursue the recommendations or not, unless the TPA is unsatisfactory. Principals/vice-principals cannot mandate additional training/workshops in areas of need therefore the process can be very ineffective. (Maharaj, 2013, p.63)

How can we design better evaluation systems that help to elevate the quality of instruction in our classrooms? Here are some recommendations for improvement:

Recommendation 5 – School administrators should receive more training

Accurately assessing and helping to improve teacher effectiveness should be priorities for all school administrators. To achieve this, administrators must receive ongoing, rigorous training that equips them to render fair, accurate and consistent assessments of teacher performance. This, in turn, will enable administrators to provide useful feedback to teachers and to design professional development programs that meet their needs. It will also instill greater confidence among teachers in the validity of their evaluations.

Recommendation 6 – Teacher evaluations should include multiple classroom observations

Evaluations should consist of multiple classroom observations, and some of those observations should be unannounced. This would provide a more accurate picture of teacher practice and would allow for more meaningful assessment and feedback.

Recommendation 7 – Impartial observers should take part in teacher evaluations

At least one observation should be conducted by someone who does not have a personal relationship with the teacher. Evidence suggests that different administrators can assign significantly different ratings to the same lesson (Gates Foundation, 2012). It would therefore be unfair to allow a teacher’s evaluation to be driven by the subjective opinion of one person. The third party could be an instructional leader, department head, master teacher or administrator from another school.

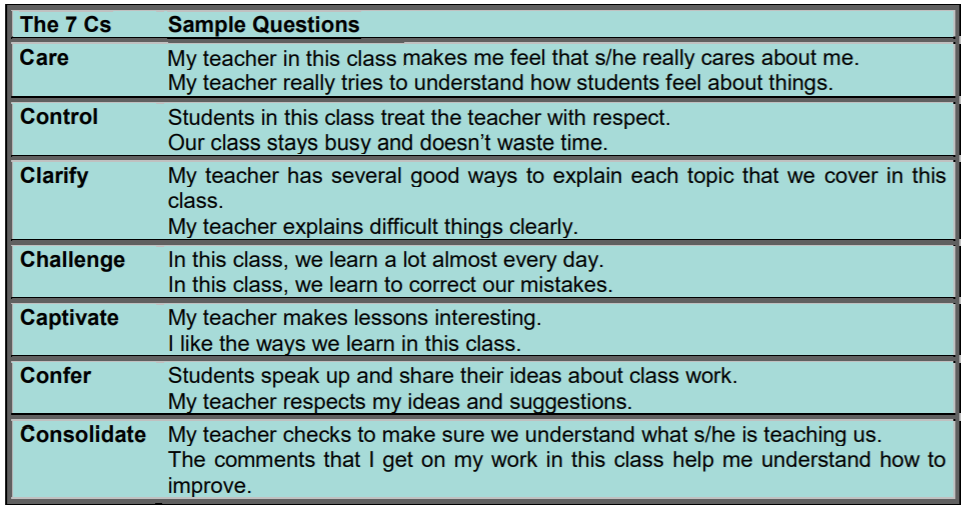

Recommendation 8 – Teacher evaluations should incorporate feedback from students

Students spend hundreds of hours in classrooms every year, yet rarely if ever are they asked to evaluate their instructors. Skeptics might wonder whether students would simply award higher scores to lenient teachers and lower scores to more demanding ones, but research indicates that this is not the case provided students are asked the right questions. Table 1 provides a sample of student survey questions that have been shown to be predictive of student learning.

As a report by the Gates Foundation put it, “[T]he average student knows effective teaching when he or she experiences it.” The report went on to say that when students report positive classroom experiences, these classrooms tend to achieve greater learning gains, and other classrooms taught by the same teacher do so as well (Gates Foundation, 2010). The results of such surveys tend to be consistent and reliable across different classes and school years, and represent a rich source of descriptive feedback that teachers can draw upon to improve their performance.

Recommendation 9 – Performance appraisals should be conducted more frequently than is the current case

Regardless of skill level or experience, teachers need and deserve ongoing feedback. More frequent evaluations enable better personnel decisions; they also help teachers grow as professionals, recognizing that a teacher’s effectiveness and developmental needs may evolve over time. At a minimum, teachers should be evaluated every two years. Among other benefits, this would help to ensure that they receive timely help with their challenges and regular recognition of their successes.

Recommendation 10 – Ratings of teacher effectiveness should use a multiple-level scale

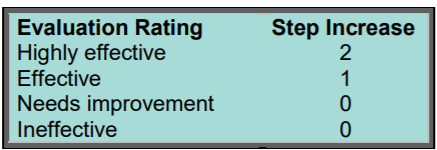

To be useful, a performance appraisal should provide the employee with a clear description of his or her strengths and weaknesses. Simply telling a teacher that his performance is “satisfactory” is not enough. As one administrator put it, “Some teachers are well beyond satisfactory and some are just satisfactory; this needs to be acknowledged” (Maharaj, 2013, p. 62). Much more useful would be a rating system with four levels, enough to convey a meaningful assessment of performance while ensuring clear distinctions between levels. A four-point scale would also allow for meaningful differentiation of teacher performance within schools and districts. An approach suggested by The New Teacher Project (2010) is to rate teachers as highly effective, effective, needs improvement, or ineffective.

It is interesting to note that although Ontario’s teacher appraisal system provides only two rating categories, the software that administrators use to conduct the assessment actually employs a four-point scale: very effective, effective, somewhat effective and ineffective. The fact that such information is not included in the final evaluation report is puzzling to say the least.

Recommendation 11 – Teacher evaluations should help drive personnel decisions

As noted above, many teachers and administrators do not take the evaluation process seriously because the results do not impact future personnel decisions. It should be obvious that for the evaluation process to have any significance, the results should be factored into all important personnel decisions, including those dealing with hiring, promotion, compensation, dismissals and layoffs.

It is in the area of staff reductions that reform is most badly required. As it now stands, schools and school boards that must lay off teachers due to declining enrollment generally let go of those with the least amount of seniority. Clearly it would be much better for students if, rather than basing layoffs on seniority, schools kept their best teachers and let go of those who have been determined to be the least effective.

Teacher Pay

Teacher salaries are the largest expense in public education, accounting for more than 62 per cent of education spending (Statistics Canada, 2012b). Salary levels heavily influence our ability to attract, develop and retain effective teachers. Against a backdrop of constrained education budgets, how we pay teachers should be of concern to all who are interested in the efficient and effective allocation of resources in the education sector.

The average starting salary for teachers in Canadian public schools is about $45,000, ranging from just over $39,000 in Quebec to more than $50,000 in Alberta. This exceeds the average across the 34 countries that belong to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). For example, starting salaries in England, Scotland, Portugal and Ireland are anywhere from three to 13 per cent lower in U.S. dollar terms based on purchasing power parity (Statistics Canada, 2012b). Given that high starting salaries serve to attract talented people into the teaching profession, this is an important strength of Canada’s public education system.

On average, the best-paid teachers in Canadian schools earn between $80,000 and $100,000 a year. While this is also higher than the OECD average, I would argue that, for our best teachers, it is too low. As previously mentioned, great teachers have been shown to increase the lifetime earning of each of their students by an average of $25,000, which translates into an increase of $600,000 in economic gain for a class of 24. In purely economic terms, therefore, one could conclude that a great teacher is worth far more to society than he or she is currently paid. Even at $100,000 a year, great teachers would represent excellent value for the money.

Single salary schedule

As significant as the salaries paid to our teachers is exactly how those salaries are determined. Teachers in Canadian public schools are paid based on what is called a “single salary schedule” (SSS). The SSS is a grid that standardizes pay for all teachers based on two variables: academic credentials and years of experience. A history of the SSS can be found in Note 1, but in summary the grid was first developed in the early 1900s to remedy the widespread discrimination and pay disparities that existed at that time among teachers of different sexes, ethnicities and grade levels.

The most obvious advantage of the single salary schedule is that is simple to administer. Under this system, almost no time is required from administration and support staff at the school level to determine teacher pay levels. Category certifications are provided by teachers’ unions, which frees up time and resources at the district office as well. And salary costs for the entire teaching staff can be forecast with a high degree of predictability.

The SSS is also completely objective, leaving no room for claims of discrimination or favouritism. The only two variables that count are academic qualifications and years of experience; factors such as ethnicity, gender, religion and sexual orientation are irrelevant. Nor does it matter how well a teacher gets along with the principal.

But in spite of its advantages, the SSS has outlived its usefulness. The idea that all teachers should be treated the same undoubtedly helped to resolve inequities in the early 1900s, but in today’s schools it has created perverse incentives. Consider, for example, the hypothetical example of a teacher in a high-needs school with a large number of students for whom English is not their first language. Should that teacher be paid exactly the same as one in a school in an affluent neighbourhood with students for whom language is not an issue? Teaching in the former setting is undoubtedly more challenging than in the latter, yet the SSS fails to recognize any distinction.

Worse, the lack of any difference in pay levels creates an incentive for teachers to try to avoid the more challenging setting. Studies show that, in general, teachers seek to transfer into schools with high-achieving, middle-class students (Falch & Strom, 2005; Hanushek & Rivkin, 2007; Lankford, Loeb, & Wyckoff 2002; Scafidi, Sjoquistb, & Stinebrickner, 2007; Smithers & Robinson, 2004, 2005). Looking at it from the other perspective, teachers tend to migrate away from schools with high concentrations of low-achieving students (Hanushek, Kain, & Rivkin, 1999; Scafidi, Sjoquistb, & Stinebrickner, 2007), low socio-economic status students (Scafidi, Sjoquistb, & Stinebrickner, 2007; Smithers & Robinson, 2005;) minority students (Falch & Strom, 2005; Scafidi, Sjoquistb, & Stinebrickner, 2007) and students with special needs (Falch & Strom, 2005).

Another deficiency of the SSS is that it offers no financial incentive for teachers to improve their performance in the classroom – to become more effective teachers. Pay is based solely on academic/professional qualifications and seniority, neither of which is a strong indicator of how well teachers actually teach. Beyond the first few years of teaching, when effectiveness does appear to increase, there is no obvious reason why teachers should receive automatic yearly pay increases – and why a lazy and ineffective teacher should be paid the same as a hardworking, dedicated and effective teacher. Excellence goes unrewarded, mediocrity goes unaddressed. We should want much better than this for a profession as important as teaching.

Teacher motivation

Of course, the issue of how teachers are paid is only relevant to student outcomes to the extent that teachers are motivated by pay and are prepared to change their behaviour in response to changes in compensation practices. Granted, teachers teach for many reasons and are motivated by a range of factors, both intrinsic and extrinsic. However, few would suggest that pay is not an important factor, and indeed the perennial cry of teachers’ unions is for more. (For a more detailed discussion of teacher motivation and pay, see Note 2.)

In summary, experience suggests that teachers are about as altruistic as anybody else and that they do in fact respond to economic incentives. Consider, for example, the Ontario government’s move recently to eliminate the right of teachers to “bank” their sick days and receive a lump-sum payout upon retirement. Prior to this reform, there was an incentive for teachers not to take sick days; the more days they banked, the higher the eventual payout. How did teachers react to the change? In Toronto they responded by taking 20 per cent more sick days than during the previous year (MacDonald, 2013; Maldonado, 2013).

In the following section, I will outline some alternative approaches to teacher compensation that would address the disadvantages of the single salary schedule. Most would be relatively easy to implement and would not require significantly more time or resources.

Recommendation 12 – Teacher evaluations should be linked to progression on the salary grid

The original intent behind the single salary schedule was to ensure fair compensation for all teachers. But even in the early years of the SSS, it was recognized that not all teachers were equally effective or deserving. In his 1926 address on the SSS, E.E. Lewis said:

There should be enough flexibility in the salary schedule to provide extra pay for teachers of extra ability. In other words, merit should be recognized, other factors being equal. Teachers should realize that the top is open. Increases should not be given automatically to all teachers who are retained in the system. Instead they should serve to secure constant improvement during the time of service. (Morris, 1930, p.33)

At the time, some school boards did link salary increases to merit. Here is a sample of clauses in the salary schedules of various U.S. school systems in the 1930s:

- “The yearly increase may be granted for successful work upon the rating of the Superintendent with the assistance of Principals and Supervisors.”

- “Annual increases shall be granted by the Board of Education only when merited by satisfactory or superior work, and on the recommendation by the Superintendent of Schools.”

- “Annual salary increments shall be given subject to the approval of the Board of Education only to teachers recommended as ‘Superior,’ ‘Very Good,’ or ‘Good’ by the Supervising Principal regardless of the ‘college unit class’ to which they shall have progressed.”

- “Teachers will be rated annually as A, B, or C by the Superintendent, with the assistance of the Principals and Supervisors. Teachers rated A or B will receive the annual increment, teachers rated C will receive one-half of an annual increment and if rated C for two successive years will receive no increase. Teachers who have reached the maximum salary and are rated C will receive $5 less per month than their regular maximum.”

- “Teachers rated as ‘Poor’ shall not be reemployed; rated as ‘Fair’ shall be reemployed for the next year at no increase in salary; rated as ‘Good,’ the teacher is automatically advanced in the schedule. Teachers of exceptional ability may be advanced beyond the maximum salary upon recommendation of the Superintendent of Schools.” (Morris, 1930, p.34)

Provided we adopt a more comprehensive system of performance appraisal in our schools, there is little reason why this approach could not be implemented in Canada while staying true to the principles of the single salary schedule. Certainly one could expect strong public support for such a move. A 2005 survey found that 92 per cent of Canadian parents favoured the idea of paying teachers according to how well they teach (Guppy, 2005).

That same year, in a report titled “Teachers Matter: Attracting, Developing and Retaining Effective Teachers”, the OECD proposed linking performance appraisals to teacher pay:

Although the principal focus of formative assessment is on teacher improvement, it can also provide a basis for rewarding teachers for exemplary performance. For example, outstanding performance and contributions could enable teachers to progress two salary steps at once. (OECD, 2005, p. 205)

This system would reward our best educators while offering incentives for all teachers to improve their performance. Table 2 provides an example of how evaluation ratings could be tied to step increases on the salary grid.

Recommendation 13 – School administrators should implement performance-based teacher compensation plans (“career ladders”)

Another approach worth considering is the introduction of what are often referred to as “career ladders”. This would involve the creation of different categories or levels of teachers, with greater responsibilities and higher pay at each successive level. Progression to a higher level would signify increased capability or competence, typically demonstrated through some combination of experience and performance appraisal. A teacher who was promoted to a higher category would generally be required to accept additional responsibilities, which might include providing enhanced learning opportunities and remedial assistance to students, mentoring other teachers, taking academic classes, attending workshops or participating in professional organizations.

How effective are career ladders? A 2007 study in Arizona concluded that student achievement was significantly higher in districts where teachers worked within a career ladder program as compared to districts that lacked such a program (Dowling, Murphy and Wang, 2007). A similar study of Missouri’s career ladder program (Booker and Glazeman, 2009b) found only a small increase in student achievement, but concluded that career ladders help to improve teacher recruitment and retention.

In addition, career ladders enable teachers to meaningfully progress in their careers while staying in the classroom. Currently, a teacher who wishes to be promoted generally has little choice but to seek to become a school administrator. This ignores the fact that the skills required to be a good teacher and the skills required to be a good administrator are often quite different. It also effectively marks the end of that individual’s teaching career, which is not something we should want for our best teachers. It is worth noting that the both the American Federation of Teachers and the National Education Association, which collectively represent most of America’s teachers, support such differentiated roles and career paths for teachers (AFT, 2012; NEA, 2011).

Recommendation 14 – School boards should offer incentives to attract highly effective teachers to high-needs schools

One of the biggest shortcomings of the single salary schedule is that it offers teachers no incentive to accept the more challenging assignment of working with at-risk students. This needs to change: schools should be able to offer a range of incentives, monetary and non-monetary, to teachers who willingly shoulder more challenging roles. Nonmonetary incentives could include such benefits as additional preparation time or smaller class sizes. While these have not been shown to increase student achievement consistently, they are important components of the working conditions that can make a particular assignment more or less attractive.

Monetary bonuses are used to attract and retain teachers in high-needs schools in many U.S. school districts as well as in countries such as Australia, Denmark, New Zealand, Chile, Peru, and Bolivia (Sclafani, 2010). For example, since 2007 the Austin Independent School District, the fifth-largest school district in Texas, has paid a minimum $1,000-a-year incentive to teachers who work in Austin’s so-called “hard-tostaff” schools, under a program known as AISD Reach. The incentive increases to $3,000 annually after the teacher has served in the school for three years and $6,000 annually after six years. An assessment of the program two years after implementation found that teacher retention rates had improved district-wide (Schmidtt et al., 2009). Additional analyses found significant differences in retention rates, albeit only among novice teachers (Cornetto, Schmidtt, Malerba, & Herrera, 2010).

It would be a mistake, of course, to focus on reducing turnover without also addressing the issue of teacher quality. That is why incentives to teach in high-needs schools should only be provided to teachers who score highly in performance appraisals or have by some other means demonstrated their effectiveness.

Recommendation 15 – School boards should not attempt to tie teacher pay to student outcomes

Pay-for-performance – or “merit pay”, as it is commonly termed – is a compensation system in which all or part of an employee’s income is linked to some measurable outcome. In the context of teacher pay, such outcomes can include student attendance rates, graduation rates, dropout rates or student grades. In practice, school systems that adopt pay-for-performance schemes tend to focus on student test scores because they are viewed as hard to manipulate and easy to compare. Graduation rates and student grades, on the other hand, can be altered by making graduation requirements more lenient or classes less demanding.

Early attempts at introducing performance pay were often flawed in that they focused on measures of student achievement at a single point in time, ignoring the fact that students’ test results are heavily influenced by their experiences outside the classroom. For example Fryer and Levitt (2004) found that black students start kindergarten with test scores that are on average significantly below those of their white classmates. Paying teachers based on outcomes over which they do not have full control is obviously unfair. It can also drive schools to exclude potentially low performing students from taking tests in order to boost aggregate performance (Figlio, 2003).

Value-added pay systems offer a better approach to measuring performance. At their simplest, such schemes measure student achievement at the end of the year and then subtract student achievement at the beginning of the year. The increase in attainment over the school year is taken as an indicator of the teacher’s performance. This emphasis on student growth and not actual level of attainment addresses the problems that arise when comparing classes of students that start the year with different sets of prior knowledge and skills. More sophisticated value-added pay schemes seek to generate a predicted achievement level for a school’s students based on a wide range of data, including prior achievement, household income and parental education levels. Teachers in schools that exceed the predicted achievement level are rewarded with higher pay than their counterparts in schools that failed to meet the predicted level.

Despite being an improvement over simple merit-pay systems that are based on onetime assessments of student attainment, the value-added approach still raises serious questions. Whether value-added measures are reliable over time is unclear. Existing research on the stability of teachers’ value-added scores suggest only a modest relationship between a teacher’s scores over time (Aaronson, Barrow & Sander, 2007Goldhaber & Hanson, 2008; Koedel & Betts, 2007; McCaffrey, Sass & Lockwood, 2008;). For example, a study that examined data from five U.S. school districts found that it was not uncommon for a teacher to score near the bottom of the rankings one year and the top of the rankings the next – and vice versa (Newton, Darling-Hammond, Haertel & Thomas, 2010). Only a small minority of teachers remained in the same rating band for two consecutive years.

Another limitation of value-added pay schemes is that standardized student tests are not administered at all levels and grades. Gratz (2010) estimates that more than half of all teachers in the United States do not teach classes that are covered by standardized tests. The figure for Canadian teachers is likely to be much higher.

However, the greatest problem with programs that pay teachers based on student outcomes is that there is little evidence they actually work. Many U.S. school districts have implemented merit pay programs with little to show for it. A review of the AISD Reach program in Austin, Texas, found that student achievement growth in participating schools was not significantly greater than in non-participating schools, except in science (Cornetto, Schmidtt, Malerba, & Herrera, 2010). A similar study in Nashville, Tennessee, found no significant increase in student achievement among its teachers, except those who taught grade 5 (Springer et al., 2010). And an evaluation of a merit pay program in more than 200 New York City public schools found “no evidence that teacher incentives increase student performance, attendance, or graduation. . . . If anything, teacher incentives may decrease student achievement, especially in larger schools” (Fryer, 2011).

In any event, teachers generally oppose merit-pay schemes. A survey of Canadian teachers found that 62 per cent did not want to see any part of their income determined by the academic progress of their students (Guppy, 2005). While opposition from teachers is not in and of itself a good reason to avoid an educational reform, it should give us pause given the issues noted above. On balance, there seems little justification for the introduction of pay-for-performance schemes in Canadian schools.

Conclusion

Canada’s public education system has historically served its citizens well, but to preserve our country’s enviable living standards we must find ways to educate our students to higher levels of achievement than in the past. One of the keys to enhancing student learning and achievement is to increase the effectiveness of our teachers. Unfortunately, current human resource policies in Canadian public schools – in particular, policies dealing with the hiring, evaluation and pay of teachers – do not align with this objective. In effect, current policies pretend that all teachers are of equal ability, when this is clearly not the case. This has been referred to as the “widget effect”: Teachers are treated as undifferentiated, interchangeable parts, as opposed to professionals with unique skill sets.

These policies must change if we are to ensure that all students have access to the highest quality of instruction, and if teaching is to be taken seriously as a profession. Spending the necessary time to hire the best teachers, and strategically assigning those teachers where needs are greatest, should be common practice. Similarly, school boards should adopt comprehensive systems of teacher evaluation, ensure that teachers are provided with the feedback they need to improve, and compensate teachers based on how well they teach. Policymakers, school leaders and teachers themselves must not hesitate to promote, recognize and reward excellence in teaching. Only then can we be assured that we are providing young Canadians with the knowledge and skills they will need to succeed in an increasingly competitive world.

Note 1 – History of the Single Salary Schedule

One of the earliest proponents of what became known as the single salary schedule was Thomas W. Bicknell, a noted 19th century American education reformer. As president of the National Education Association (NEA), Bicknell pushed for increases in teacher pay and the adoption of a sliding salary scale “based upon qualifications and experience, ranging from a minimum for beginners to a maximum for the well-established and successful instructors.” Speaking at an NEA convention in 1884, he argued that,

One of the surest remedies for the removal of poor teachers in a community is the advancement of salaries. That community will then seek better talent, and the better talent will seek the better pay. (Morris, 1930, p.1)

In Canada in the early 20th century, teachers of higher grades tended to earn more than those of lower grades, in part due to the differences in education required for these positions. While ostensibly fair and objective, this system resulted in large inequities and was subject to significant discrimination and favouritism. Women tended to occupy most elementary school teaching positions while the secondary level was dominated by men; this resulted in a considerable pay gap between male and female teachers. Women and members of racial minorities often earned significantly less than non-minority males in the same position. There were even variations in salary among non-minority males with equivalent positions.

In 1920, the Ontario Secondary School Teachers Federation passed a motion supporting the principle of “equal pay for equal work” (OSSTF, 2010). A year later, a group representing female teachers in Toronto wrote to the Toronto Board of Education requesting salaries and recognition equal to those provided to their male counterparts (“Teachers send “pay,” 1921). These sentiments, combined with growing pressure for higher levels of educational attainment among teachers, eventually led to calls for the adoption of a more consistent approach to compensation by which teachers with similar qualifications and experience would be paid the same salary, regardless of gender, race or the grade level to which they were assigned.

E.E. Lewis, then Superintendent of Schools in Flint, Michigan, in an address before the Department of Superintendence in 1926, defined the single salary schedule as follows:

The phrase “basic single salary schedule” means a schedule of salaries covering all classroom teachers in kindergarten and grades one to twelve, inclusive, regardless of sex, position, grade, or subject taught. It means equal pay for equal work, equal merit, equal length of service and equal academic and professional preparation. The term “basic” means that the single salary schedule for teachers is the one used as a basis for the building of salary schedules and for all other groups of personnel. (Morris, 1930, p.3)

As implemented in Canada – initially in academic schools and later in vocational institutions – the single salary schedule took into account only two variables: academic/professional qualifications and years of experience. It created an objective, non-discriminatory system of compensation for all teachers. (It should be noted that the principle of higher pay for each additional year of experience also aligned with worker compensation practices in the broader economy at the time.)

The single salary schedule remains in effect in Canada’s public education system today. In both elementary and secondary schools, teachers are paid based on their academic qualifications and years of experience. In Toronto in 2011, for example, salaries for high school teachers ranged from $45,709 for a first-year teacher with a college diploma to $94,707 for a teacher with 10 or more years of experience and a graduate degree or subject specialist qualification.

Note 2 – Teacher motivation

A common argument against the introduction of performance-based teacher compensation plans is that teachers tend to be motivated not by monetary considerations but by a dedication to public service. Several studies have concluded that people working in the public sector generally do have more altruistic motivations than those in the private sector (Graham & Steele, 2001; Steele 1999; Le Grand, 2003). Often these findings are based on surveys and interviews with the workers themselves, raising the question of whether respondents were engaging in what is sometimes termed “positive impression management” – answering questions the way they thought they should respond rather than revealing their true feelings. (For a discussion, see McGrath, Mitchell, Kim & Hough, 2010). And it is worth noting that a U.K. review of the evidence from studies in which on-the-job performance was actually monitored found that public sector employees do indeed work harder when there are financial incentives to do so (Burgess, Propper and Wilson, 2002).

In any event, it seems reasonable to conclude that teachers are motivated at least to some extent by pay even if other factors, such as altruism, are more important. In jurisdictions where there are shortages of teachers, there is overwhelming evidence that such shortages can be alleviated with higher teacher salaries (Dolton, 2010). In addition, a U.K. study found that the relative earnings of teachers compared with non-teaching alternatives have a marked effect on whether people will enter teaching, on whether they will continue to teach and on decisions by ex-teachers to return to teaching (Dolton, McIntosh and Chevalier, 2002). Worryingly, it appears that highly rated teachers are also the ones most likely to leave the teaching profession when higher salaries are available elsewhere – a tendency that, over time, could result in students being taught by the least able (Southwick Jr. & Gill, 1997).

References