Deficits and National Debt: What They Mean to You

Taxation policy reform and the national agenda

The case for taxation policy reform

The Business Council believes that comprehensive reform of Canada’s taxation policies is an urgent priority. Why is it important?

To begin with, many fear that the present tax system is having an adverse effect on job creation and, ultimately, on our standard of living. It is seen to distort and complicate investment and economic decision-making by individuals and by businesses, thereby inhibiting Canada’s economic growth. The federal government recognized this problem early in its mandate. In its 1984- Agenda paper, the current tax system was identified as an obstacle to growth, and reform of the tax system was seen as an important dimension of economic renewal.

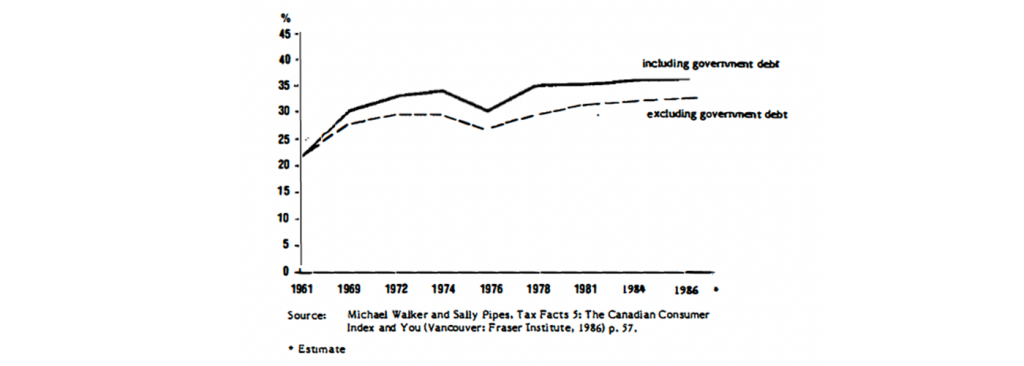

Many Canadians are disturbed by their growing tax burden. From I 961 to 1986 the total federal and provincial taxes paid by the average family grew from 22% to over 32% of its income. If budget deficits — the value of programs and services not currently paid for – – are included, this tax rate grew by more than one-and-a-half times to nearly 36%.

The Average Canadian Family’s Total Tax Rate

Some argue that the taxation system has failed because it has not yielded enough revenue to finance government operations and programs, particularly at the federal level. The resulting deficits will be a drag on the economy for many more years. Also, the system’s inefficiencies adversely affect the economy because, for example, existing taxes take more from taxpayers than they add to government coffers. Recent studies in the United States show that in the 1970s, the marginal cost to the economy of collecting one extra dollar in their progressive tax system was between $1.50 and $1.70.

Lastly, the world context cannot be ignored. Tax reform initiatives are under study or taking place throughout the industrialized world. If Canada’s tax rates and systems fall increasingly out of line with those of its competitors, most notably the United States, the consequences would be harmful to our employment and prosperity.

In this respect, it is useful to note the burden of taxation in other developed countries. In the early 1980s taxes accounted for about 35% of Canadian Gross Domestic Product compared with 30.5% in the United States and 27.2% in Japan. Although Canada ranks near the middle among countries of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in relative tax burden, it is worrisome that our two largest trading partners have significantly lower burdens.

These are a few of the reasons why Canada’s uncompetitive tax climate poses serious risks for its medium-sized, open economy and why tax reform must be carried out soon and on a comprehensive basis.

The Business Council’s proposals

This paper outlines the Business Council’s views on a national taxation policy framework and the general tax policies that will best serve the public interest and allow Canadians to prosper in an increasingly competitive world.

Canada has a large and expensive public sector. Like many Canadians, the Business Council is of the view that the overall tax burden that has grown up to support current levels of public sector expenditure is excessive. While this issue is important it is deliberately not addressed in these proposals. We do address, however, an issue that we believe lies at the heart of the tax policy reform debate — how to pay for government programs and services with the least damage to growth and job creation. Our suggestions are designed to be “revenue neutral” — in other words, if implemented as a package, they would not reduce or increase total tax revenues.

Four main elements

The package of reforms proposed in this paper centres on four main elements:

- The tax base should be broadened. Existing tax incentives and exemptions should be cut back so as to let a freer market allocate resources more efficiently.

- Income tax rates should be cut for persons and corporations. This will help save taxes for many Canadians, with particular emphasis on cutting the marginal rates at the top and for low income individuals.

- The personal and corporate income tax systems should be better integrated. This should minimize economic distortions and prevent unfairness and abuse.

- Greater reliance should be placed on transaction or expenditure taxes. This would make the tax system more efficient and encourage saving and investment.

All tax policy changes proposed by the Council in this paper are based on a coherent policy framework that sets forth key assumptions and objectives to guide individual policy choices and decisions.

A general framework for tax reform

Basic principles

The Business Council believes that tax reform should be based on the following principles:

- The prime purpose of the tax system should be to raise revenues to finance public services. In contrast, the current system is saddled with too many other tasks including promoting growth, stimulating employment, redistributing income, and fostering regional and sectoral development. It cannot perform all of these tasks well.

- The tax system must not distort the normal working of market forces in determining rewards and in allocating resources. A more neutral tax system, allowing greater scope for the freer exercise of market forces and individual efforts, would be more effective in promoting growth, job creation and business development.

- The Canadian tax system must be compatible and competitive with the systems of our international trading partners. In an increasingly global economy, our tax system must not put Canada at a competitive disadvantage nor must it cause skilled Canadians to move abroad to find more comfortable tax climates.

- Canada’s tax system must respond to the needs of society and must treat people fairly. It must foster a climate of freedom and incentive where each Canadian has the maximum opportunity to develop and prosper.

Design of tax reform

The Business Council believes that a reformed tax system should incorporate the following features:

- It should be stable and based upon an integrated and cohesive policy framework. Public confidence would be promoted, personal and business planning would be less disrupted, and tinkering with the system would be reduced.

- It should be balanced and avoid excessive reliance on any one area of taxation. The imposition of any tax inevitably leads to distortions as taxpayers adjust their behaviour to minimize their tax burdens. Taxation should be spread across a broad range of taxes, goods and services, with each revenue source taxed at moderate rates.

- The burden of taxation should be shifted away from income and towards expenditure. Taxing income leads to distortions and a loss of incentive, reducing the levels of saving, investment and effort. By contrast, taxing expenditures minimizes these effects and would help productivity and competitiveness by encouraging investment.

- “Double taxation” of corporate income — first tax ing corporations and then the dividends they pay to individuals — should be eliminated. The total tax paid should not be determined solely as a result of how income is earned or flows to its ultimate owner. The tax burden eventually falls on individuals because corporate taxes are effectively passed on through higher prices, lower wages, or a lower return on investment. Taxing businesses as if they were disassociated from the economy only hides the tax burden and reduces governments’ accountability.

- Hidden taxes should be eliminated. They raise production costs and make Canadian producers less competitive with foreign businesses both at home and abroad. Also, the public should be able to identify the taxes they pay and how they pay them.

- Our tax system should be simpler and consistent so Canadians ca n understand it and comply with it more easily. Complexity contributes to tax avoidance and evasion. Uncertainty hampers economic decision-making.

- The base of Canada’s tax system should be broadened and the whole range of special incentives, exemptions, deductions, concessions and credits should be cut back. This will help avoid costly distortions in the economy and will ensure that taxpayers and firms in similar circumstances face similar tax burdens.

- The personal income tax system should be progressive, with the top marginal tax rates a slow as possible. High or quickly rising marginal rates dampen personal initiative and risk-taking while impairing productivity and capital formation. They also encourage tax avoidance and the use of tax shelters that are often not in the public interest, socially or economically.

- The corporate tax rate should be roughly equivalent to the top rate of personal income tax. This will go a long way to achieving an appropriate integration of the personal and corporate tax systems and contribute to simplicity and avoidance of abuse.

- The tax system should not penalize taxpayers by giving the government windfall gains as a result of inflation.

- The corporate and personal tax systems should not penalize taxpayers whose income rises and falls over the years.

- The federal and the provincial governments should coordinate their tax policies as closely as possible and make tax reform a cooperative effort.